It’s been a bit since I posted last. Ideally, I would like to post once a week or every other week, but school and life have kept me fairly busy. On top of that, I recently started a job in my university’s herbarium. After a couple weeks of work, I got to thinking, I bet most people don’t even know what an herbarium is.

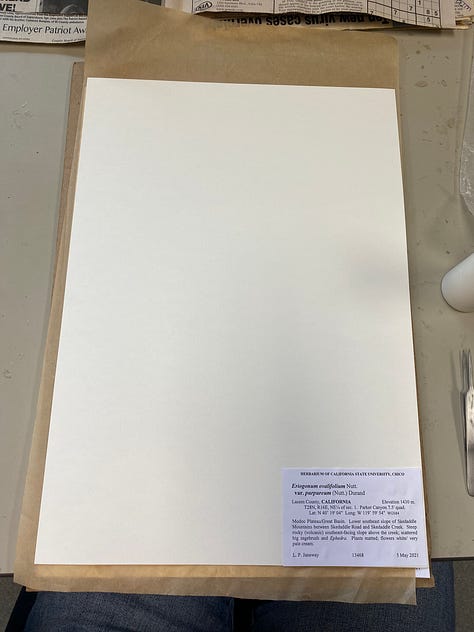

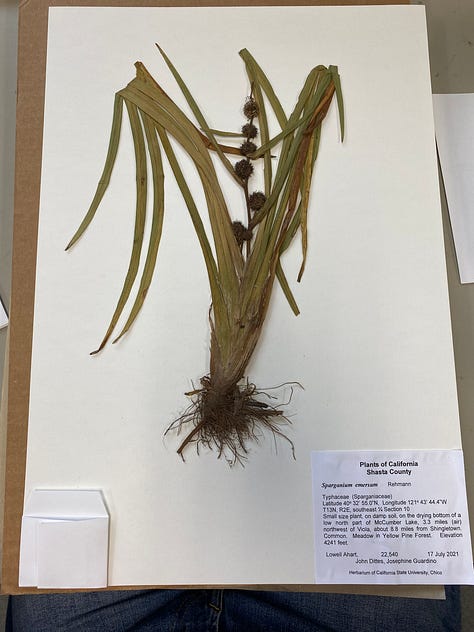

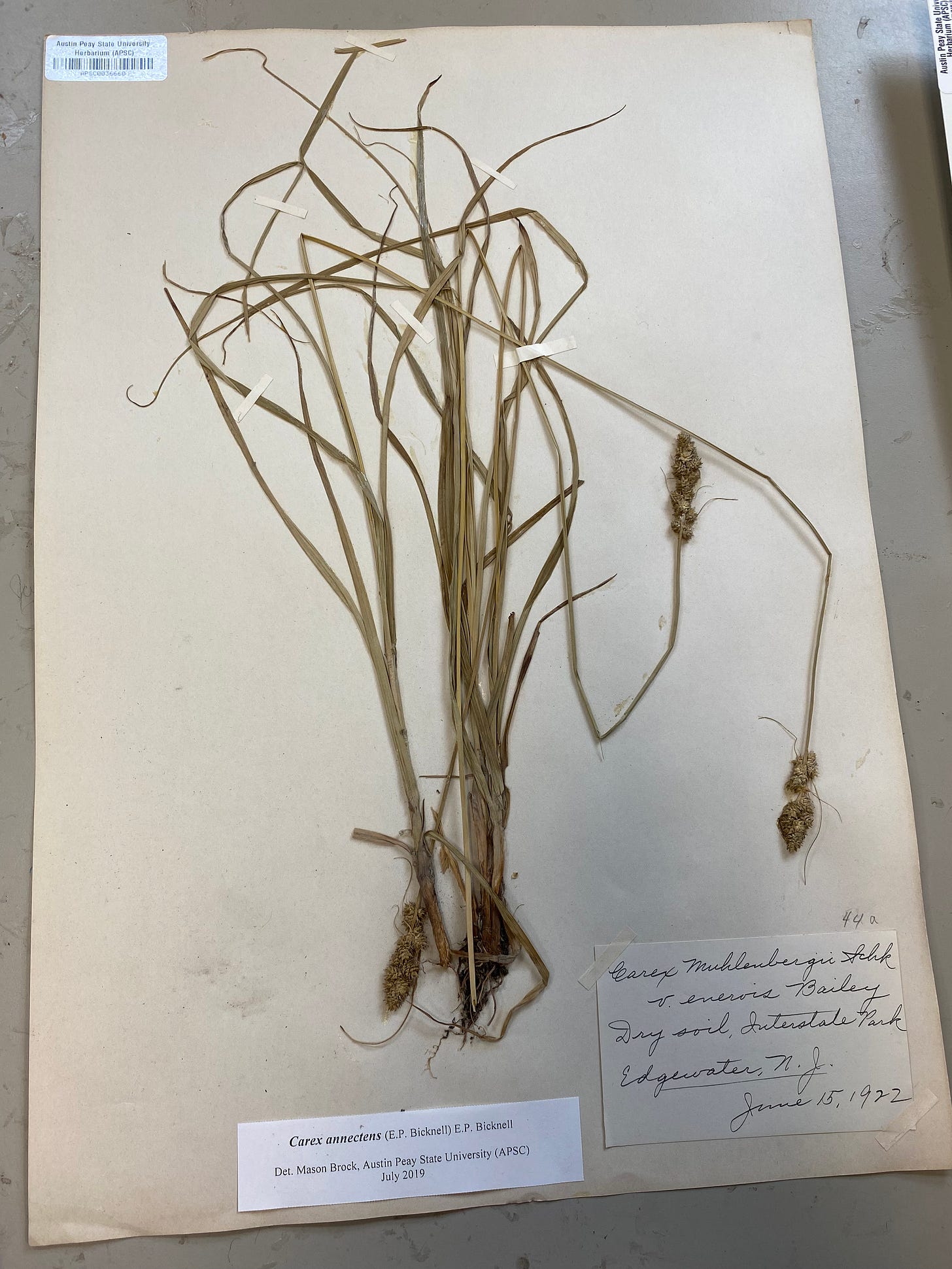

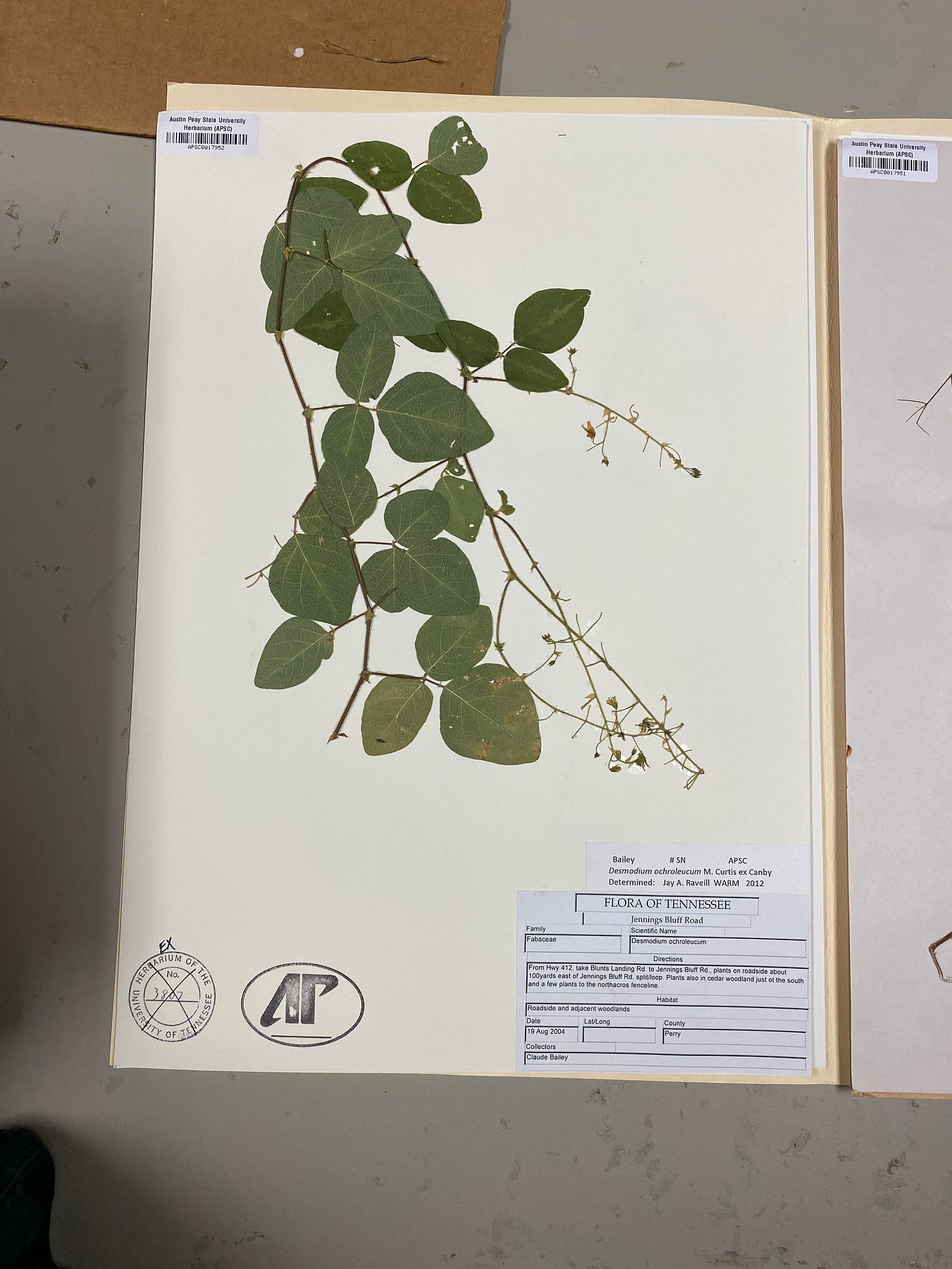

So what is a herbarium? In simple terms, it’s a library/museum made up of collections of pressed and dried plant samples mounted on paper to be preserved for long-term scientific study. These plant samples are called specimens. Each specimen contains scientifically useful information such as date, GPS coordinates, elevation, physical and biological habitat descriptions, people present, etc.

Historically, herbaria date back to the 1540s in Italy, where Luca Ghini, a physician, professor, and botanist, is credited with creating the first herbarium. Ghini would collect plants and place them between sheets of absorbent paper, press them, and once dry, glue them onto cardboard. Ghini mostly did this so that he could teach his students about plants in the winter months.

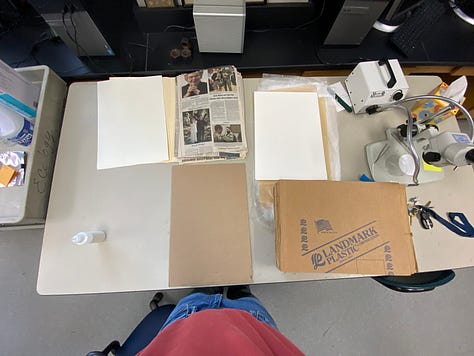

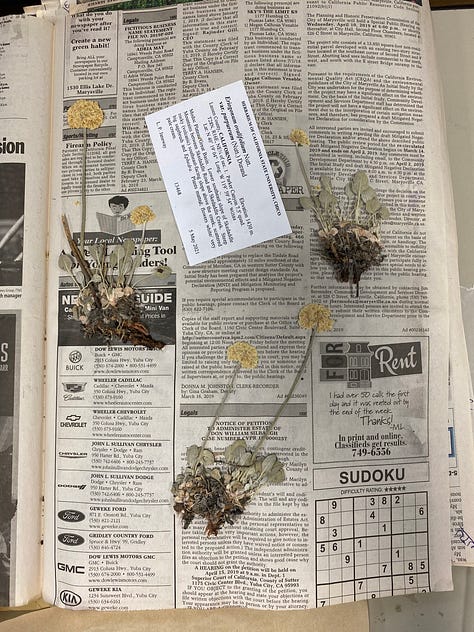

Today, little has changed in the way plants are preserved. When plants are collected, they’re placed in individual sheets of newspaper, then sandwiched between sheets of blotting paper, and finally stacked between pieces of cardboard. The whole stack is then pressed tightly between wooden frames with straps to apply pressure. After the plants are fully dried, they are frozen to kill any insects that may be present. then they’re ready to be cataloged, and that’s where I come in.

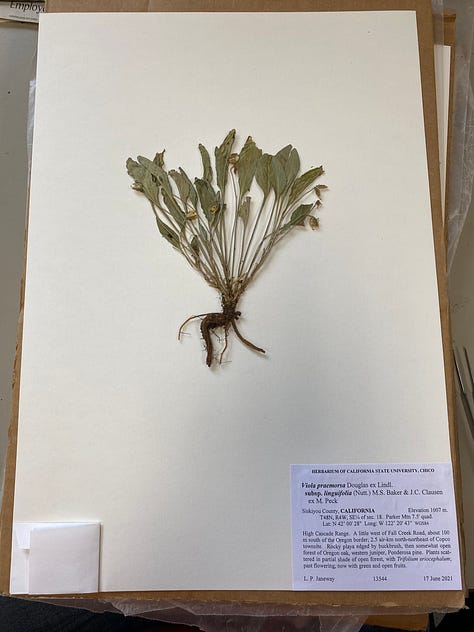

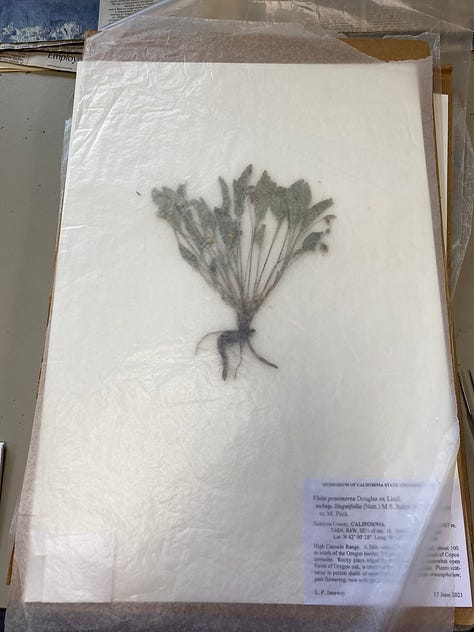

One of my jobs at the herbarium is to carefully mount (glue) dried specimens onto firm sheets of museum-grade paper. Each specimen gets a printed label with all its collection data, the who, what, where, and when of that particular plant’s story. Eventually, these mounted specimens are cataloged in a digital database and stored in protective cabinets. It’s a surprisingly delicate process, especially when working with fragile specimens. It’s also incredibly satisfying to know I’m helping preserve a tiny piece of botanical history, one that could contribute to scientific research for generations to come.

Here’s a look at my setup and some pictures of the process!

These collections serve as a permanent record of plant species, their geographic distributions, and their historical presence across different regions. This allows researchers to identify plants and study plant taxonomy (the science of classifying and naming plants. Taxonomy is a branch of biology that groups plants based on their similarities and differences, helping scientists better understand the relationships between species.

Beyond taxonomy, herbarium specimens are used in all sorts of fascinating research, including pharmacology, genetics, forensics, history, pollution tracking, and much more. Each carefully preserved plant holds data that can unlock insights into the past, present, and future. This can be anything from discovering medicinal compounds, tracing the spread of invasive species, or identifying environmental contaminants in plant tissues.

Herbaria collections also play a critical role in tracking changes in biodiversity over time. By comparing specimens collected decades or even centuries ago to plants found today, researchers can detect shifts in species’ ranges, population declines, or the arrival of invasive species. This work is especially important now, as climate change and habitat loss are accelerating changes to ecosystems at an alarming rate.

Herbaria also need our help. Many people, and even educational institutions, don’t always see the value of preserving natural history collections. Unfortunately, when these collections aren’t seen as profitable, they’re often put on the chopping block. Take Duke University, for example, where just last year, the university gave their herbarium only 1-2 years to find a new home for over 800,000 specimens. Realistically, many of these collections won’t find a permanent home, and countless irreplaceable pieces of scientific data could be lost forever.

If you’re wondering what you can do to help, go check out your nearest herbarium. Many universities and museums have one and would love to give you a tour! Consider volunteering your time, or simply help spread the word about why protecting our natural history collections matters. If you’re able, donating to your local herbarium can make a huge difference. Your support could even help fund a student worker (just like me!) who’s learning valuable skills while helping preserve these irreplaceable collections for future generations.

If you enjoy reading nature Substacks, I encourage you to check out Dr. Bob Leonard at Cedar Creek Nature Notes, Dian Porter at My Gaia, Larry Stone at Listening to the Land, Al Batt at Naturally Al Batt, and Dr. Estes at GALAS: Natural History of a Southern Conservationist

You won’t be disappointed!

“Love of nature is the spring from which stewardship flows. In contrast, disconnection from nature leads to apathy in the face of all environmental problems. A useful way to define love is sustained, compassionate attention. Paying sincere attention to, and developing a rich curiosity about others helps us to be kind. This attention takes work and improves with practice.” - John Muir Laws

Love this. Thanks!

This is so cool! I’m excited to follow you in this journey!