Limestone Glades

A Journey Into One Of Tennessee's Most Unique Ecosystems

I recently set out with my friends Holly and Jared to explore one of Tennessee's rarest grassland ecosystems. These hidden gems were shaped by millions of years of geological history. So before we get started, we need to go back roughly 460 million years to the Ordovician period.

During this time, what is now Tennessee, was covered by a shallow tropical ocean teeming with coral reefs and vibrant marine life. Many of these ancient organisms can still be found today as fossils in nearby creeks. Over time, these creatures' calcium-rich shells and exoskeletons fell to the ocean floor, where, through time, they were compressed into limestone. This first layer of rock is known as the Stone Rivers Group Formation.

Alright, stay with me here: picture a layered cake. The first layer is limestone, the Stone Rivers Group Formation. As we move through time, more layers were added; a layer of shaley-limestone, then Black Shale, followed by more shale, limestone, and chert. The final layer of the cake? Sandstone.

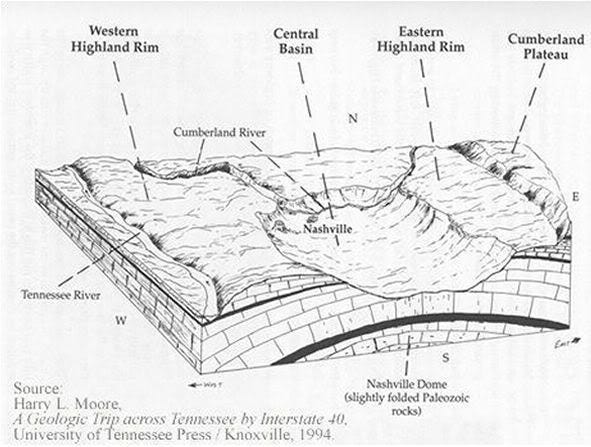

Fast forward a few hundred million years. After millions of years of tectonic plates pressing against the eastern edge of North America, the layers of this "cake" were squeezed and uplifted into a dome. The hard upper layers erode slowly, like sandstone, chert, and shale. But once the softer limestone layers were exposed with the help of this uplifting, erosion accelerated, carving out a giant bowl with a flat bottom that we see today.

Today, the exposed limestone at the center of this geologic formation has given rise to a rare ecological system known as a “cedar” glade. These systems are characterized by extremely thin, rocky soils that create challenging growing conditions. Glades are usually saturated with water in the winter and spring but become extremely hot and arid in the summer. Because of these extremes, glades are home to many fascinating and specialized species. We call these endemic species - organisms that occupy a specific geographic region and exist nowhere else on Earth, having evolved unique adaptations to survive in their particular environment.

Some of these unique species include Tennessee purple coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis), Nashville Breadroot (Pediomelum subacaule), Tennessee Milkvetch (Astragalus tennesseensis), Cedar Gladecress (Leavenworthia stylosa), Pricklypear, Widows-Cross ( Sedum pulchellum), Gattingers Prairie Clover (Dalea gattingeri) and much more! At this particular site there is also Quarterman’s Hedge-Hyssop (Gratiola quartermania), a new species described by Dr. Estes. Check out his Substack here!

.

These particular grasslands are considered partially edaphic-meaning they are maintained not by fire but by the characteristics of the soil in the glade proper. I say 'partially' because while fire wouldn’t have reached the rocky surfaces of the main glade, and would likely be detrimental to many of the species if it did, its influence increases as we move outward. Farther from the glade’s epicenter, the soil deepens, transitioning into proper grasslands, including savannas and woodlands. Historically, fire would have swept through these outer areas, maintaining their open structure.

You may have noticed that I’ve referred to these as “Cedar” glades (I and others prefer limestone glades). However, this is somewhat of a misnomer, as historically, glades did not have cedar trees. With fire suppression, cedars have encroached, choking out these once-diverse ecosystems.

Unfortunately, habitat loss hasn’t been limited to fire suppression alone. Many of these sites have also been historically used as dumping grounds and, more recently, cleared for McMansions, further degrading these fragile landscapes.

Despite these challenges, glades remain some of the most fascinating ecosystems in the region. And “cedar” glades aren’t the only ones out there! Many other types of glades exist, each shaped by unique geology and climate. These ecosystems can be found not only in Tennessee but also in Alabama, Kentucky, Missouri, and even in other parts of the world. Depending on their location, they may form over limestone, dolomite, sandstone, shale, or even volcanic rock.

It’s also important to distinguish glades from barrens, which share similarities but have key differences. While glades are typically flat and have extremely shallow soils, barrens tend to form on slopes with slightly deeper soils. Additionally, glades are often dominated by annual grasses, whereas barrens support mostly perennial grasses.

Spring is an exceptionally wonderful time to explore these ecosystems as they burst into color with a myriad of rare wildflowers. If you're in the area, Middle Tennessee has some of the best-preserved glades in the country, like Cedars of Lebanon State Park, and Long Hunter State Park.

So next time you find yourself in the Nashville area, whether it’s for a bachelorette party, honky-tonking down Broadway, or just passing through, take a break from the neon lights and check out a cedar glade. You might just discover one of Tennessee's best-kept natural secrets!

If you enjoy reading nature Substacks, I encourage you to check out Dr. Bob Leonard at Cedar Creek Nature Notes, Dian Porter at My Gaia, Larry Stone at Listening to the Land, Al Batt at Naturally Al Batt, and Dr. Estes at GALAS: Natural History of a Southern Conservationist

You won’t be disappointed!

“Love of nature is the spring from which stewardship flows. In contrast, disconnection from nature leads to apathy in the face of all environmental problems. A useful way to define love is sustained, compassionate attention. Paying sincere attention to, and developing a rich curiosity about others helps us to be kind. This attention takes work and improves with practice.” - John Muir Laws